At the end of my book launch event in New Delhi last month, a young man said something eerily gleaned from an unspoken part of my mind about the subject of my next book. T: He saved India.

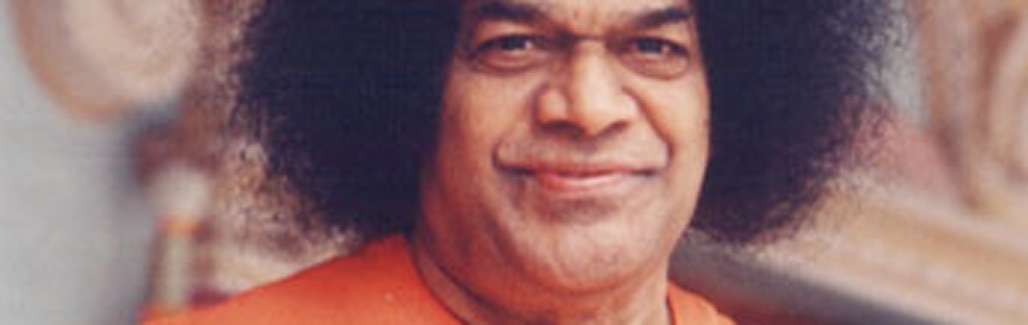

Today marks four years since my guru, God, the equivalent of a mother of a thousand, left my physical body. After all that distance and all the grief and determination, I see his life very differently than the older man I once knew and admired as much as my own father. What I see is not the God of my prayers or the zeal of those around me in the ashram, but the God of inestimable influence in the history of this land, even in hagiography. I’m just a normal person.

I see Sri Sathya Sai Baba now, as my young friend said, as the man who saved India, the man who came at a time when religion, caste, language all threatened to tear the country apart in all directions, and who kept India intact, ultimately coming into contact in some way with that common humanity.

When I first met Sri Sathya Sai Baba in 1986, I probably could not have imagined that one day I would come to recognize him in this way. My plan then was simple. Go to college, get a degree, get a job, get rich, and have fun. Everything changed for me when he joined my family. Even though I had a grudging love for him for several years, as a guru, a god, and an elder that my parents could count on to listen to me, he still felt like I had a grudging love for him. It was a huge departure from what I thought were my aspirations and goals. At best, I thought of Him as God in the facile way we all do when we long for a miracle. I prayed from time to time, but more than that, I couldn’t see myself taking his claims seriously.

Still, I think so now. What he stood for was not irrationality, superstition or India’s feudal past, as I might have been easily led to believe by my modern upbringing (or by much of the media surrounding his death). I came to believe that, but it was quite the opposite. I have listened to his peasant elders speak for years through direct poetry in Telugu and have found resonance between his writings and those of many other great teachers and guides to the spirit. Afterwards, I see his life in very clear, almost unmystical terms.

Baba spent his life not with selfish material goals, but with a very toxic world culture that teaches us violence, cruelty, and savage greed hidden behind superficial beauty. It was for the sake of decency and dignity of life itself in the face of. progress. I cannot speak of the mysticism or extraordinary power that the devotees felt in Baba, but I can speak of the objective phenomena that were also in Him. It is an incredible cultural force, a force for good, change, agency, self-reflection, critical thinking, action, service, love, and only the most arrogant kind of ethnocentric superstition. However, I believe that this can be ignored as ignorance on the part of the Indian masses.

First of all, no honest historian or serious student of Indian culture would doubt that the absurd clichés and deliberate clichés that were passed off for any objective or rational analysis in some press reports soon after his death. You’ll find more in his legacy than in the distortions. Baba’s life and works unfolded in a specific time and place. It needs to be seen not just in terms of individuals, but as part of India’s existence, way of life, survival, and way of life that somehow goes beyond simply surviving. After all, it was not Baba alone who caused this phenomenon, but millions of rich and poor people from India and abroad who came all the way from remote villages to the feet of a poor lower caste boy. It is. Dry Rayalaseema, perhaps painted by magical promises, was transformed, even if only partially, by an example of service and love. Rather than seeing the religiosity that surrounded him through the simplistic and alien theory of a primitive past that would have kept India away from noble non-Hindu terror in the future, we should see its value in our colonial past. It needs to be seen as an expression of cultural resistance that has not even been able to be liberated from the earth. Mind still enough to respect.

India was still a British colony when a teenage village boy named Satya threw away his bonds and sat on a rock at Puttaparthi to preach love and devotion. People were exposed to poverty, inequality, injustice, and fear every day. What does religion, a popular, eclectic, universal, loving, culturally expressive religion of the kind that grew up around Baba, mean in that context? After 1947, India emerged from two long and rather unpleasant experiments with religion as an imperial ideology, at best somehow calming things down to a plane of civil, secular, coexistence. We cannot forget that Baba’s life and career happened even when he was reeling. Over the next few decades, even that mundane coexistence was distorted into a strange contempt for the spiritual culture that the people of this land had spent thousands of years developing.

We were supposed to be democratic, but religious leaders like Baba earned respect and admiration from the people not through state patronage, but despite official apathy. It is another matter that in the end even the nation showed respect. His followers were able to bring water to villages and provide free medical care to the poor when the government could not. His system teaches those who see it that we have it in us, that with the right cultural leadership, given a cultural environment in which we can reclaim our sense of self, We functioned in a way that made us realize that we could work and live this way. In the messy, incompetent, post-colonial India that we experience every day, his world would be different if we truly govern ourselves and if we follow his teachings in love. It reminded us that as long as we are alive, this is what we can become.

I now understand the historical background of Baba’s life in simple and rational terms. On the other hand, we were and still are faced with the reality of a supposedly progressive global culture, its national distortions, consumerism, and greed. We live in a world where hundreds of billions of dollars are made each year by marketing certain global conditions. It is the enslavement through a mediated sense of who we are as human beings to culturally shallow, environmentally expensive, economically unjust, and socially dysfunctional ideas. It means that it is. our whole life. The cost of our enslavement is beyond our everyday understanding, but we are witnessing it. In the air you can barely breathe, in the barely edible prices of food, and in the lives of the poor still dying in villages and slums. Against all this, against the ever-encroaching shell of distraction, we had the voice of those who silently and loftily observed the ways of ancient civilizations. We have people like Baba, not as consumers, not as citizens, not as traders with God (though we necessarily started out that way), but as embodiments of love. , spoke to us as children of the immortal Son and as stewards of nature. Society and this world.

The truth is that despite colonialism, and despite decades of cultural self-destruction under the guise of secular education, India is a land of temples, monasteries, and what we in the small English-speaking world derisively call “God-men.” It means loving what you have learned to call. Millions of people living and struggling to survive in this real India, sheltered and nurtured by gurus like Baba and somehow propelled from the colonial era to the global era. People are not there to be afraid, greedy, or hypocritical like people these days. That’s what Bollywood’s preachy, pop, religious-hating pictures have become. A civilization that has elevated spiritual exploration to a sublime level in poetry, music, dance, sculpture, and indeed in everyday life, is nevertheless being held back by old colonial prejudices that prevent us from speaking. It’s really amazing how limited we are still. We speak freely and accurately about who we are and how we see this great, ancient world.

On the anniversary of the death of my beloved guru, I must ask those who are concerned about how they can help India to take Indian religiosity more seriously now, rather than dismiss it as an embarrassing relic of the past. I hope that now, a hundred PhDs and a thousand term papers will flower in our schools and universities so that the minds of tomorrow can at least learn to look, observe, reflect and grow in the world they find themselves in, without the fear of being told so. Our country’s greatest cultural realities are somehow inconsequential digressions.

Lest this all seem too vague, let’s not forget what has happened to secular projects around the world in the past few decades. Our so-called secular collapse has not produced half the fundamentalism, violence, and viciousness that experiments elsewhere have. Our so-called secular future will remain the way we have lived and become even stronger, respecting our culture, religion and all the different names we have for them. Probably. We must respect the fact that Indian religiosity is not just about superstitions and fraudsters. It has been shown that a small number (or perhaps more than a small number of criminals) have committed the crime.

In the Psi phenomenon, Indian religiosity is in fact the very human and universal that it seeks to transcend the unethical, the trivial, and the abject, by outpouring powerful, constant, and culturally rich teachings. It turns out that it’s about a desire. It’s about losing your delusion in the face of incredible reality, the grandeur of this great world, and the chance to live happily and well in it.